Suhteellisen helppolukuinen pätkä MBM:n ydinideoista.

Obesity is not a calorie problem, it is a mass problem: an introduction to the Mass Balance Model

By Anssi H. Manninen 17/5/2021

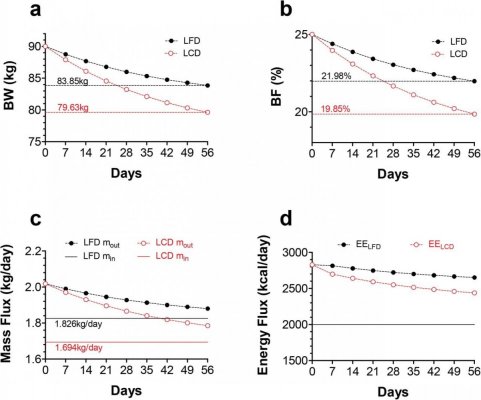

Energy balance theory is clearly erroneous

A review a by Hall [1] states: "There has never been an inpatient controlled feeding study testing the effects of isocaloric diets with equal protein [i.e., isonitrogenous] that has reported significantly increased energy expenditure or greater loss of body fat with lower carbohydrate diets.” In reality, a well-controlled inpatient feeding trial, led by Hall himself in 2015 [2], shows that a low-carbohydrate diet resulted in significantly greater weight loss both experimentally and computationally; for a detailed re-analysis, see Supplementary File 4 in [3].

Let me make MBM Research Group’s position as clear as a bottle of Finlandia Vodka®: the widely accepted energy balance theory (EBT; ”Calories In, Calories Out”) is clearly erroneous [e.g., 3,4,5]. It is possible for an open system, such as the human body, to be at mass balance while the system experiences a persistent energy imbalance. That is, energy balance may be positive (ΔE > 0) or negative (ΔE < 0) yet the mass change that may occur during energy flux is not required by the First Law of Thermodynamics (i.e., the Law of Conservation of Energy) to mirror the energy balance direction [3,4,5]. In other words, mass balance can occur in energy imbalance; see Supplementary File 2 Figure 1 in [3]. Nevertheless, numerous prominent obesity experts have strictly maintained that a low-carbohydrate diet cannot lead to a greater weight loss than an isocaloric high-carbohydrate diet – except for the small changes in body fluids – because it would somehow violate the laws of thermodynamics. However, this is certainly not the case; see Supplementary File 2 in [3].

Body mass is all about mass balances, not about energy conservation

Body chemistry – and thus body mass – is all about detailed mass balances, not about energy conservation. Our mass balance model (MBM, ”Mass In, Mass Out”) describes the temporal evolution of body weight and body composition under a wide variety of feeding experiments and provides a remarkably accurate description of experimental feeding data [3,4,5 and counting]. Unlike the EBT, our model does not violate the Law of Conservation of Mass [7]. This law dates from Antoine Lavoisier’s 1789 discovery par excellence that mass is neither created nor destroyed in any chemical reaction. The Law of Conservation of Mass holds true because naturally occurring elements are extremely stable at the conditions found on the surface of the Earth. In the everyday world of Earth, atoms are not converted to other elements during chemical reactions. The atom itself is neither created nor destroyed but cycles among chemical compounds. Ecologists have utilized this law to the analysis of elemental cycles, but – for some reason – it has been completely ignored by the obesity community.

The Law of Conservation of Mass guarantees that

1) the O2 mass that enters cellular respiration plus

2) the mass of macronutrients that served as energy fuel absolutely must equal the mass of the excreted oxidation products. Daily weight loss is, therefore, the result of daily elimination of oxidation products (CO2, water, urea, SO3) and not a consequence of the heat release upon nutrient combustion (i.e., daily energy expenditure) [3,4,5]. This must be repeated: energy intake (i.e., Calories) represents the heat release upon food oxidation, and as such, Calories have absolutely nothing to do with the body mass. Heat does not produce body mass. We can use Einstein's energy-mass equation to show, for example, that a 2,500 kcal daily diet for 100 years would increase body weight by 0.0000042kg. Thus, energy intake has no impact on body mass whatsoever.

Instead, it is macronutrient mass intake (”Mass In”) that augments body weight; the absorption of 1g of glucose, protein or fat increases body mass by exactly 1g independent of the substrate's Calories, as dictated by the Law of Conservation of Mass. The absorbed macronutrient mass cannot be destroyed and, thus, it will contribute to total body mass as long as it remains within the body. Such a contribution ends, however, when the macronutrient is eliminated from the body either as products of metabolic oxidation or in other forms (e.g., shedding of dead skin cells). Consequently, any anti-obesity intervention must

1) Decrease intake of energy-providing mass (EPM) (“Mass In”), i.e., satiating effect. EPM is the daily intake of carbohydrate, fat, protein, soluble fiber and alcohol.

2) Increase elimination of oxidation products (“Mass Out”); each day we experience a weight loss given by the weight of the energy expenditure-dependent mass loss (EEDML) plus the weight of the energy expenditure-independent mass loss (EEIML) [5]. EEDML refers to the daily excretion of EPM oxidation byproducts (CO2, water, urea, SO3), whereas EEIML represents the daily weight loss that results from i) the daily elimination of non-metabolically produced water; ii) minerals lost in sweat and urine; iii) fecal matter elimination; and iv) mass lost from renewal of skin, hair and nails [5], or

3) Both.

The Law of Conversion of Mass absolutely guarantees these facts. Obviously, this applies to any kind of anti-obesity intervention, including pharmaceuticals and dietary supplements. If a purported anti-obesity formula increases satiety, it can obviously decrease macronutrient mass intake (“Mass In”). In addition, anti-obesity compounds can increase elimination of EMP oxidation products (“Mass Out”). Increased energy expenditure has no relevance to weight management, however, so the whole concept of “thermogenic supplements” is misleading. One of my future papers will discuss this topic in more detail.

The Nutrition Facts label on packaged foods was updated in 2016 ”to reflect updated scientific information, including information about the link between diet and chronic diseases, such as obesity and heart disease.” [8]. One of the most prominent updates of the new food labeling regulations released by the FDA is found on the calorie line; the font for calories has been significantly enlarged as well as emboldened for first-glance reference. The idea behind this well-meaning update was that Caloric values can be very simply understood without having to look very deeply into the food label. Humans need, of course, energy (i.e., the capacity to do work) but Calories have absolutely nothing to do with body mass. The calorie line should be replaced, or completed, with the EMP line (e.g., “Nutrient Mass” or just “Mass”.).

Weight and fat loss loss advantage of a low-carbohydrate diet is independent of the differences in the physiological effects of the diets

MBM maintains that weight and fat loss advantage of a low-carbohydrate diet over an isocaloric high-carbohydrate diet is independent of the differences in the physiological effects of the diets (e.g., dietary carbohydrate-induced insulin secretion). Hormones cannot create mass; rather, differential weight loss simply emerges from dissimilar macronutrient mass intakes. When the energy fraction from dietary fat increases while energy intake is clamped (i.e., fixed), mass intake decreases due to the significantly higher energy density of fat in contrast to other substrates.

Ultimately, such a difference in mass intake translates into greater weight and fat loss in a low-carbohydrate diet vs. isocaloric high-carbohydrate diet. If two persons eliminate body mass at about the same daily rate, then the one ingesting less macronutrient mass will express a greater daily weight and fat loss, which over time results in a much larger body weight and fat reduction. For example, with energy intake distributed as 30% fat (9.4 kcal/g), 55% carbohydrate (4.2 kcal/g) and 15% protein (4.7 kcal/g) corresponds to a mass intake of ~487g, whereas the same energy intake sorted as 60% fat, 30% carbohydrate, and 10% protein reduces mass ingestion by ~96g. This is not a small difference. Every time the body oxidizes 1 g of glucose, for example, the heat released by the body is ∼4.2 kcals, which will not change as you age or as a function of your genome, epigenome, or proteome. Genes cannot create or wipe out mass; however, they can increase or decrease nutrient mass intake.

It has been proposed that a high-carbohydrate diet-induced hyperinsulinemia may increase mass intake (“Mass In”). A recent paper by Holsen et al. [7] seems to suggest that chronic high carbohydrate intake affects brain reward and homeostatic activity in ways that could impede weight-loss maintenance. Insulin? Ghrelin? Leptin? What ever the case, MBM makes no claims regarding the behavioral aspects of obesity whatsoever. Thus, further discussion of this topic is clearly outside of a scoop of my Commentary.

Conclusion

In summary, we would like to propose a new paradigm that paints a much more accurate picture of the evolution of body weight: Mass imbalance is the actual etiology of obesity, not energy imbalance – opening up a completely new era in obesity research. I firmly believe were are about to start a far-reaching paradigm shift, i.e., a fundamental change in the basic concepts and experimental practices of a scientific discipline. Answer the question: what do you measure when you stand on the bathroom scale, your body mass or your energy?

The immediate consequence of such a shift is that feeding studies will become much more accurate and significantly less expensive as mass measurements are cheaper and do not suffer from all the problems that energy measurements do. The whole game needs to be changed. But correcting a mistake always requires a sacrifice; and if the mistake has been great, so must be the sacrifice. If the truth has been denied for a very long time, it is quite possible that a dangerous amount of sacrificial debt has been accumulated [9].

List of abbreviations

MBM = mass balance model; EBT = energy balance theory; EPM = energy-providing mass; EEDML = energy expenditure-dependent mass loss; EEIML = energy expenditure-independent mass loss.

References

1. Hall KD. A review of the carbohydrate-insulin model of obesity. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2017 Mar;71(3):323-326. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2016.260. Epub 2017 Jan 11. Erratum in: Eur J Clin Nutr. 2017 May;71(5):679. PMID: 28074888.

2. Hall KD, Bemis T, Brychta R, Chen KY, Courville A, Crayner EJ, Goodwin S, Guo J, Howard L, Knuth ND, Miller BV 3rd, Prado CM, Siervo M, Skarulis MC, Walter M, Walter PJ, Yannai L. Calorie for Calorie, Dietary Fat Restriction Results in More Body Fat Loss than Carbohydrate Restriction in People with Obesity. Cell Metab. 2015 Sep 1;22(3):427-36. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.07.021. Epub 2015 Aug 13. PMID: 26278052; PMCID: PMC4603544.

3. Arencibia-Albite F, Manninen AH. Macronutrient mass intake explains differential weight and fat loss in isocaloric diets. medRxiv 2020.10.27.20220202; doi:

https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.27.20220202

4. Arencibia-Albite F, Manninen AH. The mass balance model perfectly fits both Hall et al. underfeeding data and Horton et al. overfeeding data. medRxiv 2021.02.22.21252026; doi:

https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.22.21252026

5. Arencibia-Albite F. Serious analytical inconsistencies challenge the validity of the energy balance theory. Heliyon. 2020 Jul 10;6(7):e04204. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04204. Erratum in: Heliyon. 2020 Sep 14;6(9):e04609. PMID: 32685707; PMCID: PMC7355950.

6. Sterner RW, Small GE, Hood JM. The Conservation of Mass. Nature Education Knowledge. 2011;3(10):20.

7. Holsen LM, Hoge WS, Lennerz BS, Cerit H, Hye T, Moondra P, Goldstein JM, Ebbeling CB, Ludwig DS. Diets Varying in Carbohydrate Content Differentially Alter Brain Activity in Homeostatic and Reward Regions in Adults. J Nutr. 2021 Apr 14:nxab090. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxab090. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 33852013.

8. FDA. Changes to the Nutrition Facts Label.

https://www.fda.gov/…/food…/changes-nutrition-facts-label (accessed 27.4.2021)

9. Peterson JB. 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos. Random House Canada, 2018.

Vaikkei sitä voi toteuttaa käytännössä, ero kalorisaannissa olisi tosiaan erittäin suuri mutta paino pysyisi stabiilina. PS. Lähden huomenna taas tien päälle mutta voi laittaa kyssiä, jos siltä tuntuu. Mulla toki läppäri mukana ja kaivan sen takakontista jossain välissä.

Vaikkei sitä voi toteuttaa käytännössä, ero kalorisaannissa olisi tosiaan erittäin suuri mutta paino pysyisi stabiilina. PS. Lähden huomenna taas tien päälle mutta voi laittaa kyssiä, jos siltä tuntuu. Mulla toki läppäri mukana ja kaivan sen takakontista jossain välissä. Vaikkei sitä voi toteuttaa käytännössä, ero kalorisaannissa olisi tosiaan erittäin suuri mutta paino pysyisi stabiilina. PS. Lähden huomenna taas tien päälle mutta voi laittaa kyssiä, jos siltä tuntuu. Mulla toki läppäri mukana ja kaivan sen takakontista jossain välissä.

Vaikkei sitä voi toteuttaa käytännössä, ero kalorisaannissa olisi tosiaan erittäin suuri mutta paino pysyisi stabiilina. PS. Lähden huomenna taas tien päälle mutta voi laittaa kyssiä, jos siltä tuntuu. Mulla toki läppäri mukana ja kaivan sen takakontista jossain välissä.